General

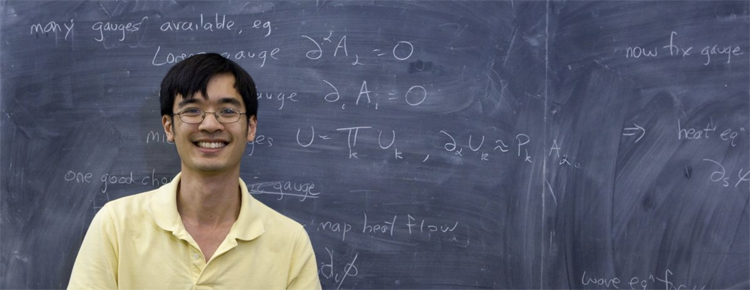

AI Will Become Mathematicians’ ‘Co-Pilot’

Fields Medalist Terence Tao explains how proof checkers and AI programs are dramatically changing mathematics.

Mathematics is traditionally a solitary science. In 1986 Andrew Wiles withdrew to his study for seven years to prove Fermat’s theorem. The resulting proofs are often difficult for colleagues to understand, and some are still controversial today. But in recent years ever larger areas of mathematics have been so strictly broken down into their individual components (“formalized”) that proofs can be checked and verified by computers.

Terence Tao of the University of California, Los Angeles, is convinced that these methods open up completely new possibilities for cooperation in mathematics. And if the latest advances in artificial intelligence are added to this, completely new ways of working could be established in the field in the coming years. With the help of computers, big, unsolved problems could come closer to being solved. Tao laid out his views on what is to come in an interview with Spektrum der Wissenschaft, Scientific American’sGerman-language sister publication.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

In one of your talks at the Joint Mathematics Meetings in San Francisco, you seemed to suggest that mathematicians don’t trust each other. What did you mean by that?

I mean, we do, but you have to know somebody personally. It’s hard to collaborate with people who you’ve never met unless you can check their work line by line. Five is kind of a maximum [number of collaborators], usually.

Read More

Nobel Prize for Katalin Karikó

Katalin Karikó received this year’s Nobel Prize for the application of mRNA techology to vaccines – she is the reason that we all don’t have to fear Covid-19 any more. In December 2022, I interviewed her for the Newsletter of Leopoldina, Germany’s national academy of sciences.

Read More

Workshop Report: Decoding Communication in Nonhuman Species II

Simons Institute for the Theory of Computing

Three years ago, in August 2020, the Simons Institute co-hosted a workshop on Decoding Communication in Nonhuman Species. Looking back at the titles of the talks, none used the AI buzzwords that have become household terms in the course of the last several months: ChatGPT, large language models, generative AI, chatbots. This past June, the Institute co-hosted a follow-up workshop, Decoding Communication in Nonhuman Species II …

We have a Momo!

Nora Coenenberg and I won the German Youth Literature Prize 2021 in in the non-fiction category for our book “100 Kinder” (“100 Children”). The award trophy is a bronze statue of Momo, the protagonist of Michael Ende’s novel of the same name. This is the video of the prize ceremony at the Frankfurt book fair on October 22.

Writing Devices

With Mary Amato and Andrea Caspari from Firefly Shadow Theater, I produced a series of videos showing writers how to use certain linguistic tricks, from alliteration to anacoluthon. My job was the animation and the video editing.

“In flow there is no room for rumination”

Credo

In psychology, the concept of “flow” is a state we attain when we enter completely into a challenging activity and forget everything else around us. It was coined by the Hungarian-American researcher Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. In his house in Los Angeles, he spoke to us about the history behind his idea, and the role that simplicity and complexity play in it.

When and how did you come up with the concept of flow?

The idea must have come when I started rock climbing in Italy, before I emigrated to the United States. I did a lot of climbing in the Alps, in Switzerland, Austria and Italy. When I came into the US at first, Chicago was completely flat, and then I discovered the Grand Tetons. In the summers, I used to take a train or a bus and get down to Colorado and Wyoming and do mountain climbing. I started writing about climbing in journals as an experience of sport, but also as a way of discovering oneself and coming to terms with life.

I think it is probably very important that you gave the phenomenon that name, “flow”.

At first it was just a feeling. One day when I was swimming in a river up in Northern California, I thought: oh, that’s the feeling that I get when I climb. And I ended up calling that the flow experience, it was a natural analogy.

Read More

Do Music Lessons Really Make Children Smarter?

Undark

A recent analysis found that most research mischaracterizes the relationship between music and skills enhancement.

IN 2004, a paper appeared in the journal Psychological Science, titled “Music Lessons Enhance IQ.” The author, composer and University of Toronto Mississauga psychologist Glenn Schellenberg, had conducted an experiment with 144 children randomly assigned to four groups: one learned the keyboard for a year, one took singing lessons, one joined an acting class, and a control group had no extracurricular training. The IQ of the children in the two musical groups rose by an average of seven points in the course of a year; those in the other two groups gained an average of 4.3 points.

Schellenberg had long been skeptical of the science underpinning claims that music education enhances children’s abstract reasoning, math, or language skills. If children who play the piano are smarter, he says, it doesn’t necessarily mean they are smarter because they play the piano. It could be that the youngsters who play the piano also happen to be more ambitious or better at focusing on a task. Correlation, after all, does not prove causation.

The 2004 paper was specifically designed to address those concerns. And as a passionate musician, Schellenberg was delighted when he turned up credible evidence that music has transfer effects on general intelligence. But nearly a decade later, in 2013, the Education Endowment Foundation funded a bigger study with more than 900 students. That study failed to corroborate Schellenberg’s findings, finding no evidence that music lessons improved math and literacy skills.

Schellenberg took that news in stride while continuing to cast a skeptical eye on the research in his field. Recently, he decided to formally investigate just how often his fellow researchers in psychology and neuroscience make what he believes are erroneous — or at least premature — causal connections between music and intelligence. His results, published in May, suggest that many of his peers do just that …

Where the Wildfires in Northern California Came From

Zeit Online, 10/13/17 (in German)

The recent wildfires in Northern California were the worst in history. Three factors led to the catastrophic effects.

So schöne Sonnenuntergänge wie in den vergangenen beiden Tagen hat San Francisco lange nicht erlebt. Glutrot hing die Sonne in den Abendstunden über der Stadt, eine fast unnatürlich erscheinende Färbung. Ursache für das Naturschauspiel sind die Aschepartikel in der Luft. Die kalifornische Metropole, sonst bekannt für die kühle Meeresbrise, die vom Pazifik weht, verzeichnet seit Tagen eine Luftqualität wie Peking. Die Schulkinder dürfen in der Pause nicht draußen spielen, es sind weniger Radfahrer auf den Straßen zu sehen, Gesichtsmasken sind ausverkauft …