Zeit Online

(This is an extended version of the interview in Zeit Online – I thought some of the parts that were omitted might be interesting to readers.)

Is the internet broken? Tech evangelist Tim O’Reilly doesn’t think so. He still believes in its positive effects. A conversation about cheetahs, elephants and Donald Trump

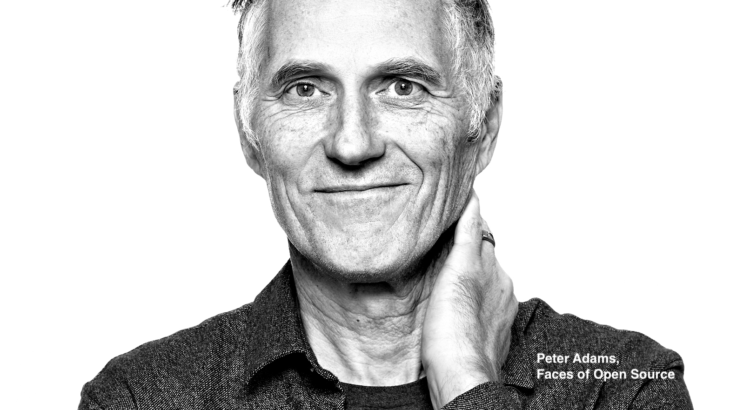

Tim O’Reilly has coined terms like “Web 2.0” and “Open Source” and has been called the “Oracle of Silicon Valley”. As founder and CEO of O’Reilly Media, he has published several books on topics such as Windows, Twitter and Unix, for example. In his latest work, “WTF? What’s the Future and Why It’s Up to Us,” he writes about what he calls the “Next Economy.” In an interview with ZEIT ONLINE, he speaks about artificial intelligence (AI) and the internet status quo.

Mr. O’Reilly, would you rather be governed by a president like Donald Trump or by artificial intelligence?

That depends a lot on which AI. Just like it depends on which person.

Why?

There are likely going to be many types of AI, just like there are many types of living beings. And they will have different abilities. A horse can beat a human in a race, and so can a cheetah. But a human being can do many things they can’t. So let’s talk about specific skills.

Can you give an example?

Would you trust directions from Google Maps more than those you get from an average person on the street? I know I would. So I can certainly imagine an algorithmic intelligence that I would trust more than Donald Trump to manage our foreign policy or our economy.

Everybody has such a high bar for what true AI is. Why are we holding AI to a higher standard than we hold people? Are people really conscious? Think about how many autonomous behaviors we have. So why do we demand that an AI be conscious? Do people have true unsupervised learning? Without supervised learning, our children don’t turn out that well. Why are we asking that our AIs will only pass the test if they have completely unsupervised learning? The most likely path to AI may well be through hybrid AIs of humans and machines, which is kind of what we’re already doing.

You said at some point: our economy is running an algorithm already. Just not the right one.

There are some real parallels between the way that our current algorithmic systems work and corporations. Both are optimization engines. Google’s Search uses hundreds of algorithms – including some deep learning algorithms – to optimize for relevance. Did the person find what they were looking for, as shown by the fact that they didn’t repeat the search? Our economy is also built around optimizations. The Federal Reserve tries to optimize employment levels and inflation, and above all to keep economic growth increasing.

And we’ve already demonstrated how we’ve told these machines to optimize for the wrong things. Facebook told its algorithms to optimize for the amount of time spent on the site, to find content that people found engaging. They had the idea that it would bring them together. We now know that they were wrong. Likewise, starting in the 1970s, our companies were required to optimize for shareholder value, on the theory that it would make our society more prosperous. But we now know that economists like Milton Friedman who pushed that idea were wrong. Companies keep optimizing for shareholders, even when it is harmful to workers, to the environment, to society. We have built a generation of paperclip maximizers, to use Nick Bostrom’s image. (He posited a future self-improving artificial intelligence, running a paperclip factory. It has this overriding goal, to make paperclips. And as it gets smarter, it still has this goal, and eventually decides that people are in the way of it making as many paperclips as possible.)

This is the biggest risk of AI: we tell the machine to do something and it does it regardless of the consequences.

My initial question was referring to an idea you wrote about in 2011: You proposed something you called “algorithmic regulation,” the use of algorithms in government. What good would that do?

That’s right. The name was unfortunate. Technology companies have learned something profoundly interesting – that you measure outcomes and then adapt really, really quickly, based on this new data. Adaptation is one of the hallmarks of intelligence. You have new data and you change your mind. Typical government regulation, by contrast, is set in motion and is expected to be good for 10, 20 or 50 years. That doesn’t work anymore. Whereas in a Silicon Valley kind of environment with a program that is literally being updated multiple times a day, hundreds of times a day, a little test creates a feedback loop so things are constantly getting smarter. We need to help government learn faster from its mistakes.

Typical government regulation is set in motion and is expected to be good for 10, 20 or 50 years. That doesn’t work anymore.

Tim O’Reilly

For example, Trump’s big tax break for corporations in 2018 was sold as having the goal to get more investment from American companies – give them a tax break and see how that works out. It turns out they didn’t invest. So if in your terms you have a goal, you take a measure and then you measure whether what you intended happens – and if it didn’t happen, you take away the tax break again, right?

That that is exactly what you would do. And in fact, what you would do if you were really doing it intelligently, you’d do a bunch of tests before you rolled it out to everybody. But of course progressives understand that nobody in our political system actually thought a corporate tax cut was going to have that effect. That was just a cover story, a spin. I don’t believe that our politics are based on a sincere belief about those economic outcomes. Some self-interested parts of society said “Oh, it will be better for us, so you should do it.”

Will China be the first country that uses algorithms and AI seriously in government? They don’t have the democratic impediments.

Possibly. I do think that China has some pretty serious problems on its own. I was just over there, and there appears to be a kind of Ponzi economy there, in real estate in particular. They’re continuing to build to keep people employed, but there are empty buildings everywhere. Overall, though, I do think that there is a level where we have some serious questions about whether democracies are the right way to move forward. Marjorie Kelly, who I’m a big fan of, said one of the things that we got wrong was we built a political democracy without an economic democracy. We have an economic oligarchy to go with what was supposed to be a democratic system. And the oligarchic economy tends to trump democratic politics.

I like an idea that Kevin Kelly came up with back in 2011, which is that we should be working towards what he calls a “protopia”, not a utopia. A society that is continually getting better. It’snot perfect, it’s not “Hey, we got it all figured out”, but just that we’re progressing.

Paul Cohen, who used to be the DARPA program manager for AI and is now the Dean of the School of Information Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh, said “The opportunity of AI is to help humans model and manage complex interacting systems.” These systems can help us be smarter and more responsive.

The ultimate complex problem is climate change and its consequences, right?

That’s exactly right. And one of the defining things that we’re going to see in the 21st century in addition to climate change is the conflict between countries with declining populations and lots of robots and countries with a rapidly increasing young population and not a lot of robots. Instead of humanity as a whole fighting against the robots it is going to be the humans with robots versus the humans without robots. And it is most likely that the societies that have lots of young people and not a lot of robots are going to be the ones who are climate refugees. And the rich countries are going to be using their robots to help keep them out.

How do we use these new tools proactively to get ahead of some of these problems? I’ve lobbied Google for example: “You’ve gotta be kidding me – you want to build the city of the future for rich tech workers in Toronto? Go build the super refugee camp of the future. Figure out what does it look like to turn them into settlers instead of refugees, making refugee camps into productive cities. Could you turn a Syrian refugee camp into the next Singapore, except the Singapore of sustainability? That would be a goal worth going for, because we’re going to have hundreds of millions of people who have to be resettled.”

If you look at these big problems on a political level, what they have in common is that you have to do something now about a system that you don’t completely understand.And the people who pull on the brakes are always saying: we don’t even understand it yet, how can you do this or that? I think in the algorithmic world, that’s a familiar situation, right?

That’s right. You’re learning as you go, and learning faster is the name of the game.

I don’t think deep learning is the be all and end all of AI. It may in fact be a dead end for a lot of purposes, but the ability to respond to data that you don’t completely understand does seem to be one of the characteristics of these systems. You feed in a whole bunch of data, you’re telling it you’re looking for something but you don’t know how you find it. And that’s pretty cool.

But the political system isn’t set up for this kind of rapid decision making.

Then maybe we need a new kind of political system.

What might that look like?

If you think of Google as the government of the web, they have criteria for when they consider a web page to be useful: how many people link to it, how much time people spend there, whether they return to the search and so on. They have built a system where they say: This is what good looks like. When Google noticed in 2011 that all the content farms …

… providers that are producing and publishing a huge number of articles or videos with the goal of generating as many clicks as possible …

… were coming up with lousy content that Google thought was good, they updated their algorithm and basically wiped out a whole lot of these companies. I am a fan of a stronger, more principled government that really works for the people. And that does mean rapidly reevaluating things.

“I don’t think opposing something is the right response”

Google can do that from one day to the next, but governments often can’t.

But if we think about what better government would look like, it would be more data driven and decisive about its goals. Instead, we have this crony capitalism where interested parties have too much influence. It’s as if the way Google dealt with spammers was to sit down with them and agree how much of the pie they would get. When people say, “We need to fix the internet,” I say: No, we need to fix the fact that there are groups of people who have very narrow special interests, people who are holding the world hostage and keeping us from doing the right thing on issues that matter a hell of a lot to everybody else. Quite frankly, we need government that is focused on the public interest in the same way that tech companies, at their best, are focused on the interests of their users.

Using the impassionate intelligence of machines to achieve goals that we as humans set sounds like a great thing. But these systems are sometimes quite controversial. In the U.S., for example, you have AI playing a role in the criminal justice system, having a say in who has to stay in jail and who gets paroled. A lot of people are very much against handing such decisions over to machines.

I don’t think opposing something is the right response. All of these predictive policing algorithms of the police and the justice system have shown us the amount of bias in our system. The algorithms are bad because we have trained them based on decades of biased input. To say, “the systems showed us that we had been screwing up in the past, so instead of improving them, let’s hand decisions back to the people and to the systems that produced the data that trained the algorithm badly” – that’s not right.

You have always been considered an optimist about technology, especially when it comes to the internet and its empowering and liberating forces. But in the past few years, there has been a tech-backlash. Social media companies, especially, have been criticized: Their methods of microtargeting users, showing them individual ads based on sensitive personal information, are believed to have played a role in radicalizing and manipulating people. Has the backlash made you second guess some of the convictions that you hold?

Not really. The internet is being scapegoated in a lot of ways.

For example?

In their book “Network Propaganda,” Yochai Benkler and his colleagues at Harvard looked at the transmission of conspiracy theories on the internet, and they found that theories originating from the leftist fringe were tamped down by leftward-leaning mainstream media, but that fringe ideas originating on the right were amplified by rightward-leaning mainstream media. Micro-targeting misinformation through Facebook may have been a marginal factor, but quite frankly, institutionalized misinformation by so-called traditional media was probably way more influential. Do I want Facebook to get better? Yes. But do I also want the New York Times to get better? Do I want Fox News to get better? Absolutely

But aren’t Facebook and all these other tech companies more powerful today than Fox News or the New York Times?

I do think a lot is wrong with the platforms. But I also think if you contrast Facebook with Pharma or Big Oil or Big Tobacco, they’ve been pretty responsive. Facebook has hired tens of thousands of people to check fake news and they’re spending massive amounts on technical innovation on all of these issues. Compare that response to, say, the response of tobacco companies to what we learned about lung cancer, or the response of fossil fuel companies to climate change, or pharmaceutical companies to the opioid crisis, or Wall Street banks to nearly sinking the world economy back in 2009 – tech comes off looking pretty good by comparison. We are scapegoating Facebook in particular. You don’t hear as much about YouTube, and YouTube is probably at least as bad or worse. I do wish that we were having a more nuanced and data-rich conversation about this as opposed to: “Let’s pretend that we have a culprit and lynch them and move on and make sure that nobody looks too closely at all the other players in the system.”

We are scapegoating Facebook in particular. You don’t hear as much about YouTube, and YouTube is probably at least as bad or worse.

Tim O’Reilly

But it’s not just about the political ads on Facebook, it’s also about other ways technology has been used. It’s about opaque algorithms, facial recognition, cameras following your every move and people tracking you on the internet. All of that has generated a feeling of powerlessness.

I struggle with facial recognition in particular. There are dystopian possibilities there, no question. It’s a pretty fraught technology in a political context. A repressive regime can use it to track people: I think we’re already seeing some pretty dark stuff in China on the basis of facial recognition. But in general, there are also really positive possibilities. Would I like my car to be looking at me to see if I’m dozing off? Absolutely.

“The big problem is the massive asymmetry of power”

Would you like your insurance company to know that as well?

The way I think about all this is: It’s not having the data that’s the problem, it’s whether the people who have it are using the data for me or against me. This whole idea of “we have to stop people from having data” is the wrong approach. Healthcare privacy is a big deal because insurance companies discriminate. We don’t have to stop collecting data, we have to stop the discrimination. Even though it might not be simple.

But still: We don’t know who is getting access to the data and what companies are doing with it.

I think part of the solution is going forward, not back. The big problem that we have today with all of these systems is the massive asymmetry of power. We have to find ways to empower people so that they are more equal to these big systems. Could I have a machine that was clearly just designed to work for me, to protect me, to look after me, to express my preferences? People are starting to think about a personal AI that has as its mission: “I’m looking out for Tim,” and “I’m protecting him from all the other machines that are trying to take advantage of him.”

Let’s take the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as an example: Ever since it has been in place, every website presents you with this cookies disclaimer that we don’t even read, but we click “ok” anyway. What could a machine do to improve this process?

What you want is a machine that negotiates with the other machine, because then it can, in fact, understand, what data a system wants. And I will say that some of the companies have gotten quite a bit better. For example, on Android, Google now gives you pretty granular visibility into which apps are asking for your location and then asks me if that’s OK. And that’s great. Google’s working for me.

But self-regulation usually doesn’t work with companies. They always promise to do better, but only rarely change. Can you really leave it all up to them?

Probably not. That is a role for government, but also for a kind of adversarial element in the private sector. Ad blockers are a kind of technological response. And they are just the beginning of this sort of defensive, personal-agent technology. I could certainly imagine a great technology platform that arises around that promise and that will be the next equivalent to Firefox.

There is a group in Germany that came up with a digital rights charter for the future. Do we need something like that?

I’m skeptical of most of these digital charters. The people who are coming up with those charters don’t really understand the technology deeply enough. And they’re coming up with things that sound good but aren’t actionable. That’s not to say that good things might not come out of it. But I’ve been in a lot of discussions where I just feel there’s a lot of blind men and the elephant: Everyone sees part of a story, but nobody is looking at the big picture.

And so these are just aspirational statements without any teeth. The answer to bad code isn’t a written charter, it’s code and law that enforces that charter.

Has the European data protection discussion had some effect on the American debate?

I think so. Although mostly it has come across as an inconvenience to companies. It’s a greater inconvenience to small and mid sized companies than it is to the really big ones.

Every company that has a global business basically has to adjust to European law. That’s a great political success.

It is, but it’s not necessarily a good policy. Take the ways that it affected my company. For example, we do our Foo Camp events, and GDPR has made it much more difficult for us to invite Europeans, because before, whenever we heard heard about this cool, interesting scientist, we could just send them an invitation. Now we have this whole process to find somebody who can make an introduction – here we are doing something that people would probably like to receive from us if they did get it, and we can’t send it to them.

It’s a typical example of what we talked about earlier: a big piece of legislation comes out, and then the first thing people notice is all the quirks and all the counterintuitive things that are happening. If you could turn the knobs and adjust these things …

We do tend to have an adversarial regulatory framework – don’t do this, don’t do this, don’t do this. And we also have a system of various economic incentives, but they’re really disconnected, and we really need to be building a single integrated system.

In government we have that embryonically in the tax code and in subsidies. They are analogous in many ways to the algorithmic interventions made by Facebook and Google to shape the systems they operate. Free market fundamentalists say that government should keep its hands off the market, without acknowledging that the market as it currently exists is deeply shaped by existing policy.

So they decry things like the electric vehicle tax incentive as a market intervention without recognizing all of the subsidies that already exist for fossil fuels! In tech, we look at the systems we build, and change them when they aren’t meeting their objectives. That’s why renewable incentives are great, but they’d be even better if we phased out fossil fuel incentives at the same time. And there is so much more possibility for nuance. For example, electric vehicle incentives are phased out once a manufacturer gets to scale. At that point the incentive is no longer needed. And California just phased out the electric vehicle incentive for cars above a certain price because most of the incentive went to rich people who don’t need it. More nuance. That’s good.Or think about the obesity epidemic in the US – it is the product of farm subsidies that make corn syrup the cheapest form of calories. This is a very fixable problem.

It’s about the little farmers in the Midwest.

No, it’s about the big farmers in the Midwest. Again, that’s political spin. I don’t want to sound like I’m a fan of of autocrats, though. I’m a fan of stronger, more principled government that really works for the people.